Mogilev Governorate

About Mogilev or Mahilyow

The All-Empire census conducted in 1897 provides a sharp and clear picture of the demographic structure of the city. Out of a total population of between 41,100 and 43,119 inhabitants, 21,539 were Jews – close to 50% and even more. This figure places Mogilev as one of the central cities in the Pale of Settlement where Jews constituted a plurality or a small majority. This fact is of crucial importance for understanding the social, economic, and political dynamics in the city.

Read more…

Beyond their demographic weight, the Jews of Mogilev were the backbone of the city’s economy. They played a central role in the city’s extensive trade networks, mainly in grain, leather, and timber, and maintained connections with major port cities such as Riga and Danzig. At the beginning of the 20th century, Jews owned 219 small factories and 92 out of the 93 distilleries in the city. The craft sector was also largely dominated by Jews, with the tailoring branch being particularly prominent. This economic concentration created a unique social structure, in which Jews were not only an ethnic group but a fundamental economic class without which the city’s life could not be described.

Mogilev became an important center of the “General Jewish Labour Bund,” a secular socialist party founded in 1897. It argued that the future of the Jewish people lay in the struggle for a socialist revolution and national-cultural autonomy in Eastern Europe, rather than in emigration. At the same time, the Zionist movement gained a strong foothold in the city, and Mogilev produced prominent Zionist figures, such as Joseph Vitkin, whose call published in 1905 was a formative appeal for pioneering settlement in the Land of Israel.

In October 1904, Tsarist soldiers conscripted for the Russo-Japanese War carried out a pogrom against the city’s Jews. Later, the First World War and the revolutions that followed were a historical watershed for the city. In August 1915, following Russian defeats and the advance of the German army, the “Stavka” (the headquarters of the Supreme Command) of the Russian army was moved from Baranovichi to Mogilev. This move transformed the quiet provincial capital into the military, and in effect also the political, heart of the Russian Empire until its collapse.

After the Bolsheviks seized power, the “Stavka” in Mogilev briefly became a center of anti-revolutionary activity. The last non-Bolshevik commander, General Nikolai Dukhonin, was lynched in Mogilev by a mob of revolutionary sailors in December 1917, after he refused to negotiate a ceasefire with the Germans. This brutal murder on the platform of the city’s train station symbolized the violent transfer of power. The “Stavka” was officially dismantled in March 1918, after the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Jews of Mogilev did not experience the revolution as a distant event; they witnessed the beheading of the empire on their doorstep, an experience that was simultaneously terrifying and fundamentally unsettling.

The post-revolution period was a time of chaos. Mogilev was briefly occupied by Germany in 1918 and became a battlefield in the Civil War. The Bolsheviks captured the city in 1919 and incorporated it into the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The turmoil of the Civil War brought with it a new wave of anti-Jewish violence. Crucially, during this period, a pogrom occurred that was carried out not by “White” armies or nationalists, but by elements from the Bolshevik camp.

The 1920s in Mogilev were characterized by a “violent struggle” between the “Yevsektsiya” on the one hand, and the religious and Zionist circles on the other. This was not an equal struggle; backed by the power of the state and the secret police (the Cheka), the “Yevsektsiya” systematically dismantled the structures of Jewish life. Its actions included closing synagogues, confiscating communal property, and suppressing religious schools (yeshivas and “cheders”).

The Bolshevik Revolution destroyed the economic base of most of the Jews of Mogilev, who were merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans. Soviet policy aimed to transform this “unproductive” “petty bourgeoisie” into a proletariat of industrial and agricultural workers. It can be agreed that by 1929, Mogilev was no longer a “Jewish city” in the deep sense it had been in 1897. It had become a Soviet city where many Jews lived, but their communal autonomy had been eliminated, and their fate was now entirely in the hands of the state.

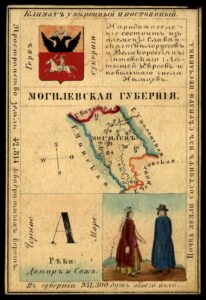

Mogilev Province – back view of a card from the geographic card set illustrating all provinces of the Russian Empire as it existed in 1856. Each card presents an overview of a particular province’s culture, history, economy, and geography. Mogilevskai︠a︡ gubernii︠a︡ (Mogilev Province) depicted on this card corresponds to part of present-day Belarus. It contains a map of the province, the provincial seal, information about the population, and a picture of the local costume of the inhabitants. For the front view of the card and more information visit the Library of Congress Online Catalog