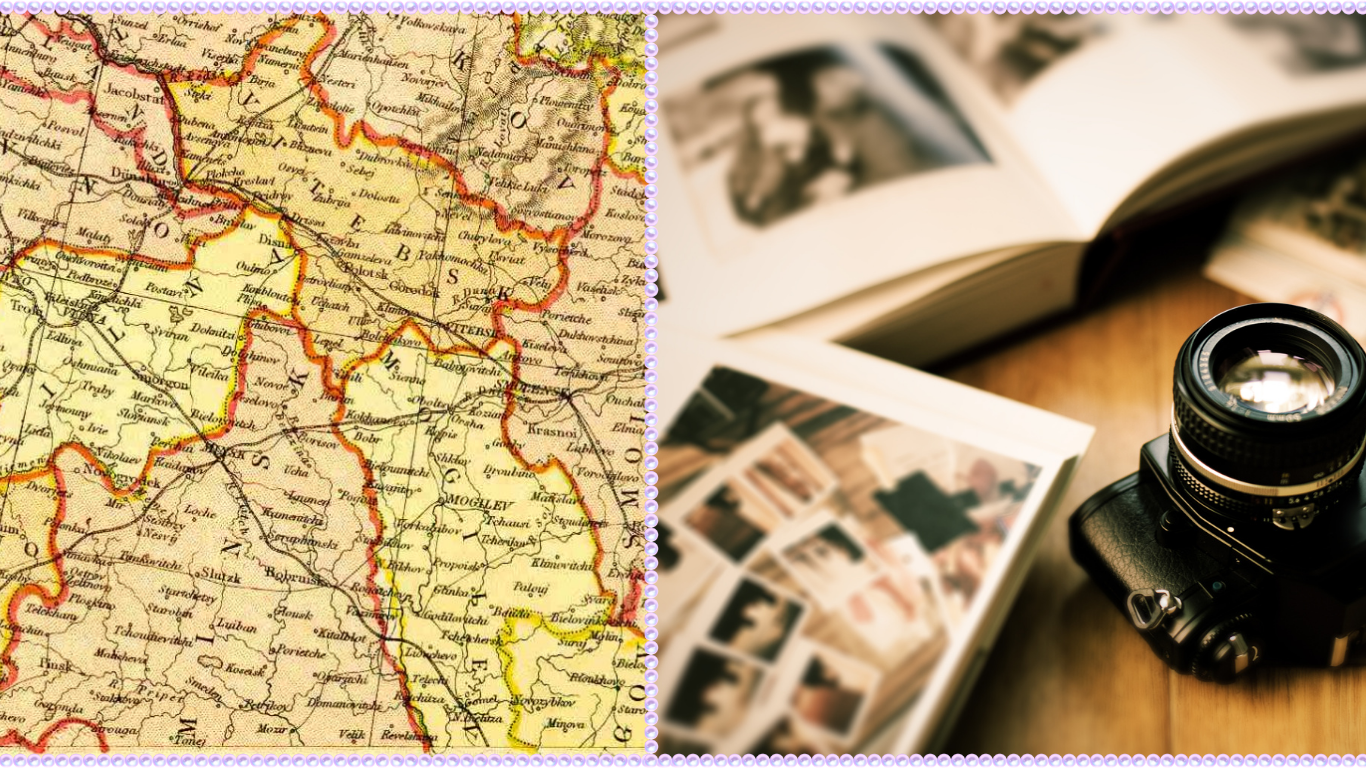

Vilna Governorate

About Vilna

Vilna, or as it was known in the Jewish imagination, “Jerusalem of Lithuania” (Yerusholayim d’Lite), was not just a city, but a symbolic and conceptual space of the highest order in the Jewish world. In the period under review, 1875 to 1929, it embodied a dual and complex heritage: on the one hand, it served as a fortress of traditional rabbinic scholarship, a heritage shaped by the revered figure of the Vilna Gaon; and on the other hand, it became the cradle of modern and secular Jewish politics.

Read more…

Vilna served as an important commercial center, thanks to its location at a crossroads of railways and rivers. Jews played a dominant role in many sectors, including commerce, crafts, and finance. The 1897 census showed that about half of the city’s 64,000 Jews earned their livelihood from industry, crafts, and transportation. The main industries included clothing manufacturing, paper and printing, leather processing, and wood products.

In the early 20th century, the Jewish community of Vilna experienced a turbulent and contradictory period, characterized by inter-religious tension alongside unprecedented political and cultural flourishing. The decade opened with dramatic events that soured the atmosphere in the city. The blood libel of 1900, in which David Blondes was accused of ritual murder, agitated the community for two years until his acquittal. Political tension reached another peak in 1902, when the Bund activist, Hirsh Lekert, attempted to assassinate the city’s governor, becoming a symbol of the revolutionary struggle. External events like the Kishinev pogrom (1903) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904) further heightened the sense of insecurity.

Despite the dangers, Vilna became a vibrant arena for nationalist and socialist movements. The Zionist movement flourished, and the city served as the center of its activities in Russia. Major Zionist newspapers such as “Ha’Olam” were printed there, conferences were held, and it hosted senior leaders, chief among them Theodor Herzl in 1903.

Surprisingly, it was precisely during this period that liberal governors like Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky were appointed to the city. They cultivated positive relations with the Jewish community leadership, eased decrees, and offered hope for change. This period of flourishing lasted until 1911, when the Russian authorities began to suppress Zionist activity and put the members of the Central Committee on trial.

During the First World War, Vilna was under a harsh German occupation, which brought great suffering to all inhabitants, and especially to the Jewish community, which suffered from hunger, forced labor, and financial extortion. The leader of the Jewish relief committee, Yaakov Vygodsky, refused to cooperate with the occupying authorities and was eventually imprisoned in Germany. Upon their retreat, the Germans recognized Lithuania’s independence.

After the German withdrawal, the city plunged into a chaotic period of violent changes of power. It was conquered by Polish nationalists (who killed 80 Jews but also granted political rights), then by the Soviet Red Army, and finally, it was handed over to sovereign Lithuania. Vilna, which was the historical capital of Lithuania but had a Polish majority, stood at the heart of a conflict between the two states. Poland resolved the conflict through a “staged rebellion”: in 1920, the Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski conquered the city and established a supposedly independent “republic.” This entity soon voted for unification with Poland. The League of Nations recognized the annexation in 1923, and Vilna remained under Polish rule until the Second World War, while Lithuania moved its provisional capital to Kaunas.

The crowning achievement of cultural life in Vilna during this period was the founding of the Jewish Scientific Institute (Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut, YIVO) in 1925. The institute, founded by scholars such as Max Weinreich, was intended to serve as the central academic authority for the study of Jewish life in Eastern Europe, with a special emphasis on the Yiddish language and its culture. Its establishment sealed Vilna’s status as the unofficial capital of “Yiddishland.”

Vilna Province – back view of a card from the geographic card set illustrating all provinces of the Russian Empire as it existed in 1856. Each card presents an overview of a particular province’s culture, history, economy, and geography. Vilenskai︠a︡ gubernii︠a︡ (Vilna Province) depicted on this card corresponds to part of present-day Belarus. It contains a map of the province, the provincial seal, information about the population, and a picture of the local costume of the inhabitants. For the front view of the card and more information visit the Library of Congress Online Catalog